Undertones: Turkish citizens rethink what democracy means

Translations

Illustration by Global Voices

This story is part of Undertones, Global Voices’ Civic Media Observatory‘s newsletter. Subscribe to Undertones.

Welcome back to Undertones, where we analyze media narratives from around the world. This week, Turkish researcher Sencer Odabaşi breaks down what the conversations are like on Turkish Twitter following the reelection of President Erdoğan. Some of the most vivid reactions are aimed at LGBTQ+ groups.

On June 25, LGBTQ+ groups and individuals will march through the streets of Istanbul, Turkey, fully aware that they may encounter police violence. Sencer Odabaşi explained to me that “everyone knows they will go outside and that they will get attacked. But for them, it is a statement to still go out and not allow violence to be normalized.”

June holds historical significance for pride events in Turkey. Once home to the largest pride marches in the Muslim world, Istanbul saw these celebrations banned in 2016. And as Erdoğan secured victory in Turkey's presidential elections for the third consecutive time, the stakes in 2023 are higher. Many Turkish citizens are wary of how authoritarian narratives saw a quick uptick since Erdoğan’s reelection, but also seek other venues to exercise democracy.

The conversations happening in post-election Turkey

This narrative in a nutshell: “Erdoğan thinks he can do whatever he wants now that he won again”

A significant portion of Turkish citizens (47.86 percent of the electorate, as indicated by the ballots cast for Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, Erdoğan's opponent) who wanted a change in leadership was sorely disappointed. Their cautiously optimistic atmosphere was shattered after the first round on May 14, and subsequent results only reinforced their concerns. Many now find their fears about Erdoğan and his allies validated. During his victory speech, Erdoğan targeted LGBTQ+ people and the opposition, instead of his usual more unifying tone.

“Erdoğan's terms have traditionally started out relatively softer and progressively became more aggressive, peaking during the election campaigns,” Odabaşi wrote in our database. “Directly attacking the opposition from basically day one points towards a new strategy”.

An example of how this narrative spreads online: “Those who wanted to watch the movie Pride were detained!”

Where it is shared: Twitter

Author: KaosGL, one of Turkey's oldest and biggest LGBTQ+ rights NGOs.

Content: KaosGL tweets about a police raid on BEKSAV, an İstanbul based culture and art foundation, after they refused to comply with the governor's ban on publicly screening the 2014 British movie “Pride.”

Context: On June 7, as part of their Pride month calendar, BEKSAV announced their plan to organize a screening of the film “Pride.” However, Governor Muhittin Pamuk, appointed by Ankara, issued a ban on the screening. Despite the ban, BEKSAV declared that they would not acknowledge it and invited everyone to attend the screening. The police forcefully intervened and detained several organizers from BEKSAV, who were later released. BEKSAV’s stand inspired other similar groups to also screen films that day.

Subtext: There is no subtext

Civic Impact: +3, the highest positive score on our scorecard. Coverage of the attack on BEKSAV has a positive civic impact because it is important not to normalize authoritarian pressures by the AKP.

See more related items here: 491, 494, 496, 518

See what the pre-electoral mood was with our newsletter

“What do onions have to do with the Turkish elections?”

This narrative in a nutshell: “Voting is not enough; we need to organize”

The opposition widely acknowledges that Turkish elections lack fairness due to various factors, such as the suppression of the free press, the misuse of state resources for campaigning purposes, and the government's control over the supreme electoral council. These measures make people doubt the legitimacy of Turkey's electoral process. Still, the main opposition party, the Republican People's Party (commonly known as CHP), always pointed to the ballot box as the democratic solution and discouraged citizens from protesting. Many now feel let down by this approach, and by the CHP.

As a result, a narrative has emerged urging individuals to participate in NGOs (such as LGBTQ+ groups), informal associations, unions, neighborhood solidarity groups, and political parties instead of relying solely on voting every five years. Some groups, such as the Workers’ Party of Turkey as well as other parties and NGOs, have confirmed to Odabaşi that there has been an uptick in registrations since the elections. This narrative puts into question what democracy means.

“Whether this represents a fundamental change in the Turkish political landscape or if it is just an emotional reaction to the unexpected results that will have a short lifespan, time will tell,” Sencer Odabaşi wrote on the database. “The sentiment remains civil and democratic, there are no calls for coups or international pressure/sanctions.”

An example of how this narrative spreads online: “We draw the line here, again”

Where it is shared: Twitter

Where it is shared: Twitter

Author: An anonymous pro-HDP Twitter user, @the_dartagnan

Content: They tweeted a 2016 speech by jailed pro-Kurdish HDP politician Selahattin Demirtaş questioning the legitimacy of elections under Erdoğan and claiming that “democracy is in the streets.” The tweet went viral and the video clip was shared by other accounts as well. The HDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party) is a leftist, pro-Kurdish party.

Context: The speech was made in September 2016 in the parliament, when Erdoğan was calling for a referendum and/or early elections for a presidential system, which he later narrowly won. Demirtaş was imprisoned that year and remains behind bars without having had a trial. Kılıçdaroğlu pledged to free him, while Erdogan ruled it out.

Subtext: This account claims that Turkish elections under Erdoğan should be considered illegitimate.

Civic Impact: +2 out of +3, because in an environment where any sign of dissent is criminalized, reminding the people that democratic rights go beyond just voting every five years has a positive civic impact.

See more related items here: 491, 511, 512

This narrative in a nutshell: “The opposition should behave like we want them to”

Erdoğan and his allies have employed strong anti-opposition campaign slogans for a long time, such as labeling the opposition as terrorists. However, far from abating after the elections, this narrative has strengthened.

“The main reason Turkey has not become a completely authoritarian state akin to Russia or Azerbaijan is the existence of an actual opposition,” Sencer Odabaşi says. “From Erdoğan's point of view, this narrative is about the importance of creating a controlled opposition like the one in Russia. This opposition will be tasked with criticizing the day-to-day affairs of the government while not bringing the fundamental pillars of Erdoğan's regime into question.”

For Odabaşi, the aim is not to establish a puppet opposition, but rather one that understands the boundaries it cannot cross. In Turkey's case, this means refraining from criticizing nationalist and religious conservatism, foreign policy, and Erdoğan himself. Issues concerning Kurdish and LGBTQ+ rights would also be off-limits within this framework.

“They could, however, accuse Erdoğan of not being conservative and nationalistic enough,” Odabaşi says. “Refugee policy can also be criticized.”

There are violent calls online against the CHP and the HDP. Their figureheads may face more harassment through defamation and imprisonment in the near future. For example, far-right party MHP recently called for the prosecution of opposition leader Kılıçdaroğlu because of his “links to terrorism.”

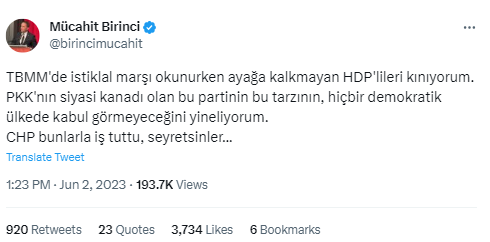

An example of how this narrative spreads online: “I condemn the HDP members who did not stand up during the national anthem in the Turkish Grand National Assembly”

Where it is shared: Twitter

Author: Mücahit Birinci, a member of the highest official executive body after party leadership (Central Executive Board)

Content: Mücahit Birinci claimed that HDP parliamentarians did not stand up for the national anthem during the opening ceremony of the new parliament on June 2, 2023. He also criticized the CHP's collaboration with HDP, which he calls the political wing of the Kurdish armed guerilla movement, the PKK.

Context: There is a recording of the event showing every member of the parliament standing up for the national anthem. It is hard to call this comment unintentional misinformation since Birinci, as a high-ranking AKP official, was certainly watching the ceremony. Pro-state media also fanned the flames by claiming that HDP members did not sing the anthem, which is not a requirement per parliamentary rules. The timing of these two provocations suggests that this was an organized communications strategy.

Subtext: Birinci implies that HDP members have a problem with the foundations of the Turkish state because they are collaborating with terrorist groups.

Civic Impact: -3, the lowest score on our scorecard, as it is an open lie to criminalize and delegitimize the opposition.

See more related items here: 492, 493, 517

Support our work

Global Voices stands out as one of the earliest and strongest examples of how media committed to building community and defending human rights can positively influence how people experience events happening beyond their own communities and national borders.

Please consider making a donation to help us continue this work.